An OKR should measure the outcome, not the work

Develop your outcome muscles by learning to separate outcomes from projects and project metrics

Welcome to another article in our series about building outcome-driven organizations and getting results from OKR. If you haven’t read the first article yet, I recommend starting there.

This post is also available in Portuguese for my friends in Brazil.

Most companies are getting a due date overdose without realizing it.

As the VP of HR at a global consumer goods company told me:

70% of our employees’ individual goals involve a project due date. And we’re not even talking about major strategic projects, but smaller deliverables that alone don’t mean much.

Overusing due dates builds a culture that values shipping projects over making a difference.

It also hurts investment returns and kills innovation. Leaders can't see which investments are working or not, while employees are treated as order-takers with no empowerment.

This due date epidemic is so pervasive that even leaders who think they have mastered OKR often fall into it. I remember an email exchange with a CEO from a fast-growing "scale-up”:

CEO: We have an advanced level of maturity with OKR. Here are the OKRs for our company and our two product lines.

Felipe: People often think they "already know" OKR, but, unfortunately, it's an illusion.

The most common pitfall is using OKR to track projects and due dates instead of achieving outcomes. You are also falling into this trap—everyone does.

In a preliminary assessment:

8 of the 19 company "Key Results" are project-based. For example, “Implement the new process in Salesforce by June.”

5 of the 13 "Key Results" from product A are project-based. For example, “Implement the new mobile app MVP by March 30th.”

8 of the 15 "Key Results" from product B are project-based. For instance, “Develop and deploy the new churn prediction model in Q2.”

You also need to focus. There's a lot going on.

CEO: I didn't realize that. These seemed like good OKRs to me. I guess we need more help than I imagined.

Your company is likely in a similar situation, with many OKRs (or goals) focused on meeting project deadlines.

To solve this problem, we have to develop new muscles and mindsets.

Leaders and employees must develop the skills needed to focus on outcomes, while the organization must develop the capabilities and mechanisms to enable those skills.

Leaders and employees also have to unlearn the mindsets that contributed to this situation.

In this article, we'll begin to develop your outcome muscles and mindset.

First, let’s do a quick recap. Feel free to skip to the next section if you've just read the first article in this series.

Recap

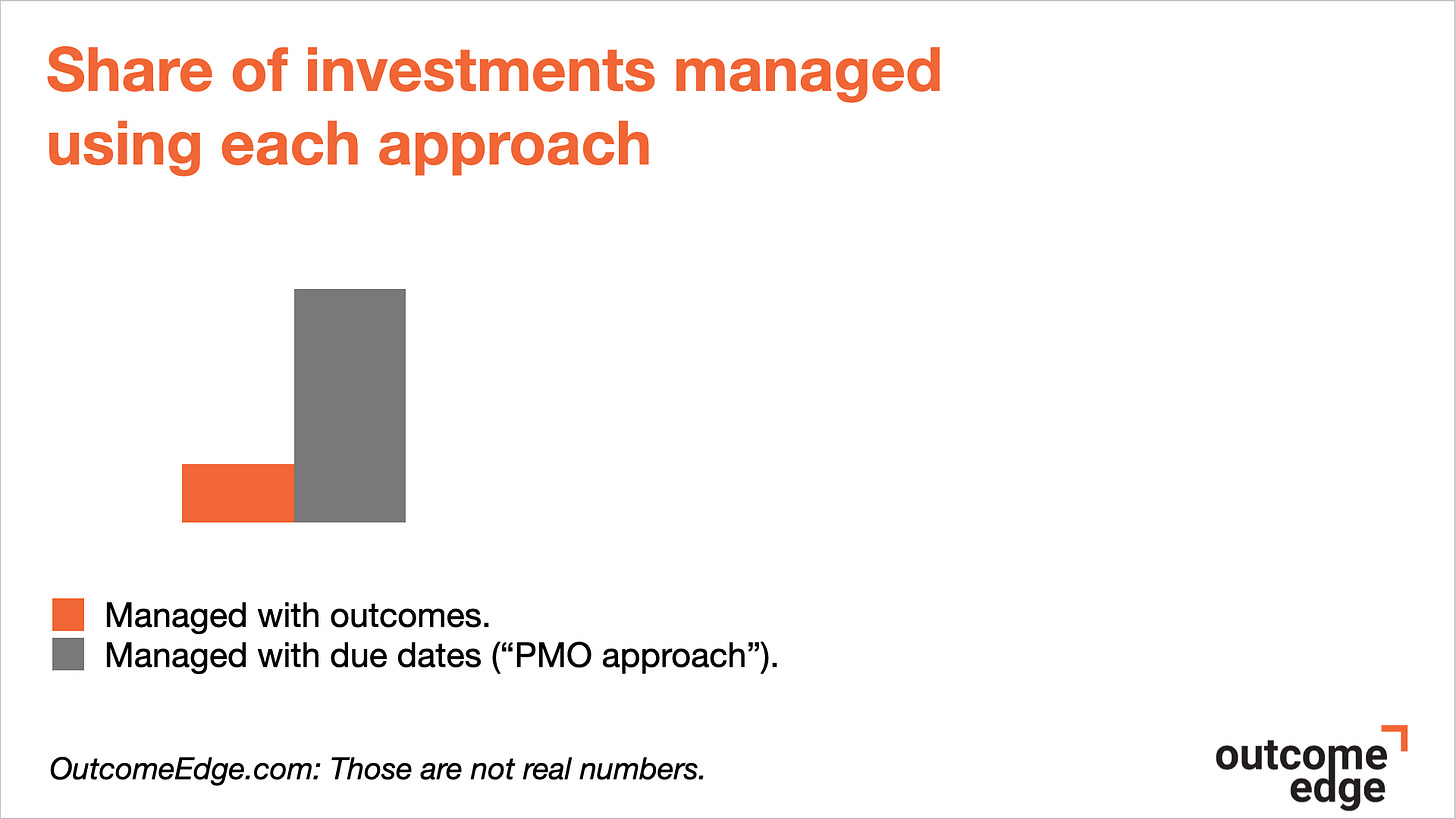

All companies use two approaches to manage work. One approach focuses on achieving outcomes, while the other simply focuses on meeting due dates. In the due dates approach, it doesn’t matter if our projects made a difference or not.

The problem is that your “outcome muscles” are probably too weak, while your “due date muscles” are too strong.

This weakness makes your organization lean too heavily on due dates, especially when paired with the wrong mindsets.

Most organizations focus a large share of their investments on meeting due dates and implicitly assume all projects will generate results.

The first step to solving a problem is to recognize it exists

The first step in developing your outcome muscles is learning to separate outcomes from projects and project metrics. Why is that important?

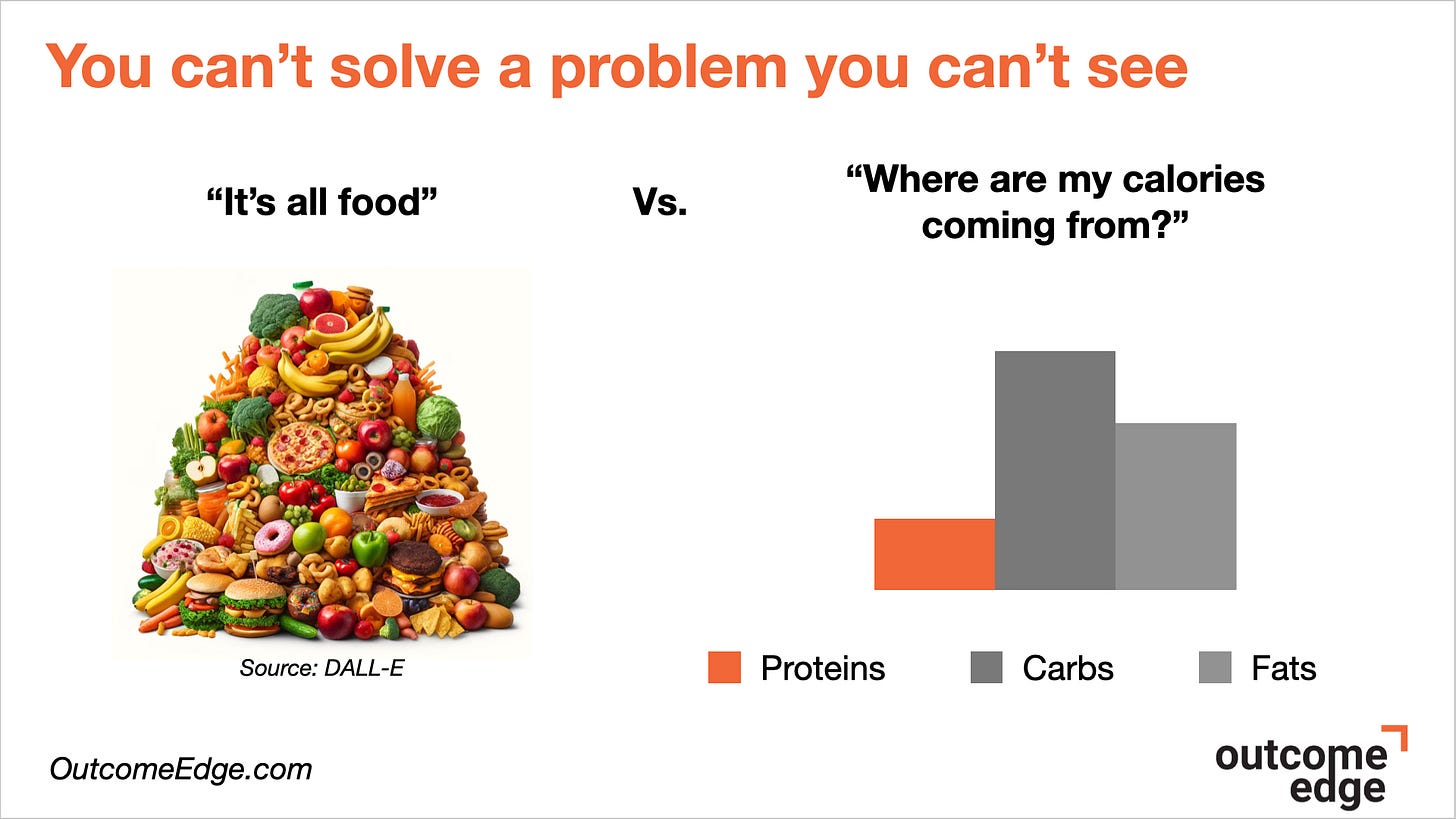

You can't solve a problem you can't see.

Imagine your doctor told you to eat healthier, but you didn't know how to differentiate junk food from healthier options. Pizzas, burgers, meat, chicken, fruits, vegetables—to you, it's all food.

Improving your health in this situation would be very hard.

Now imagine that your doctor helped you learn the difference between proteins, carbs, and fats and to pay attention to where your calories come from.

As you begin to do that, you start to see how you're doing today and where you can improve.

This story may seem a bit far-fetched, but most organizations are in a similar situation with OKRs. They want results but don't know how to differentiate "junk food” OKRs from healthy ones. They act as if anything could be an OKR.

The consequence is that these companies have difficulty understanding where their investments are going. Are we investing to achieve outcomes or just meet due dates?

These companies' Key Results include outcomes, projects, unimportant metrics, non-measurable things, and anything else you could think of. Sometimes, it's hard to understand what they mean.

Even the #1 book on OKR, Measure What Matters, acts as if anything could be an OKR. Here's an example from the book:

OBJECTIVE

Institute a culture that attracts and retains A players.

KEY RESULTS

Focus on hiring A player managers/leaders.

Optimize recruitment function to attract A player talent.

Scrub all job descriptions.

Retrain everyone engaged in the interviewing process.

Ensure ongoing mentoring/coaching opportunities.

Create a culture of learning for development of new and existing employees.

There's not a single number in the whole OKR. There are no metrics to measure outcomes or track progress.

This is just a list of projects and vague, generic phrases that sound nice but don't clearly define the intended outcome.

For example, what's the use of saying that you'll “focus on hiring"?

I can imagine the conversation inside the company:

Manager: Hi John, have you hired any A players?

John: No, boss. But I'm really focused on it. And that's all I have to do according to my Key Result.

Something similar is likely happening in your company right now. It's not your fault, but you need to fix it if you want to get results from OKR.

The first step is learning to distinguish outcomes from projects and also distinguish outcomes from project metrics.

Projects are what you do, outcomes are the measurable benefits created by what you did

There's a lot of confusion around what outcomes are. Luckily, I've found a precise and actionable definition inspired by Robert M. Penna's work with nonprofits:

Outcomes are the measurable benefits we want to create.

These include the benefits you want to create for your customers, your organization, or other employees.

Outcomes change the conversation, framing it around two questions:

What benefit do we want to create?

How will we measure it?

Separating these two questions is important because it makes it easier to first think about the qualitative benefit you want to create and then figure out the metrics.

For example, let's say the benefit we wanted to create was to make our app easier to use.

Possible metrics we could use in this case include:

Number of support requests.

Percentage of users successfully completing account registration.

Time spent to complete a purchase.

Separating outcomes from projects

We need to make the crucial distinction between projects and outcomes:

Projects are what you do.

Outcomes are the measurable benefits created by what you did.

I'm using “project” as an umbrella term for everything we do, big or small. This includes activities, tasks, programs, initiatives, deliverables, actions, epics, features, backlog items, etc.

For example, “Redesign the account registration flow" is a project. “Make our app easier to use” is an outcome (with different metrics associated with it).

The key distinction is between things that you do and the measurable benefits created by what you did.

If it can go in your backlog, it's not an outcome

There's a powerful litmus test to separate projects from outcomes:

If it can go in your backlog, it's not an outcome.

Outcomes are the consequences of what you did. An outcome is not something that you can do—or put in your backlog.

Projects are not the problem—the problem is focusing on projects

When people first learn about outcomes, they sometimes think projects are “bad.” But we need to work on projects to achieve our outcomes (of course).

Projects are not the problem. The problem is focusing on projects.

As Marty Cagan told me:

The outcomes approach is about focusing on the difference we want to make and never losing sight of it.

However, people often focus on projects even when the desired outcomes are clear and easy to measure.

A client's story illustrates that:

One day, a startup CEO found that the number of new sales leads was way below target and website traffic was down.

She decided to question the Head of Marketing:

CEO: The number of new leads is way below target. And the website traffic is falling.

Head of Marketing: But we’ve hit our OKR. We published 15 posts and three videos, did two webinars, and met all the due dates.

CEO: But the leads and traffic are terrible.

Head of Marketing: But these are not in our OKR!

The intended outcome was not only easy to measure, but the company was already tracking it. Not all cases are that simple, but this situation happens more often than you imagine.

When the project is just a means to achieve the outcome

When we focus on projects, we act as if the goal is delivering them.

But being outcome-driven is believing that we work to make a difference, not just complete projects.

That means that most of the time, delivering the project is not the goal—the project is just a means to achieve your desired outcome.

(We'll discuss how to handle the specific cases where the goal is delivering the project in our next article.)

Our brains are wired to think about projects, so focusing on outcomes requires conscious and deliberate effort.

One powerful trick is pausing and asking:

Is this project really our goal or just a means for achieving an outcome?

Is this project just an idea for achieving the outcome?

The table below contrasts seeing the project as the goal versus seeing it as a means to accomplish the outcome.

Focusing on outcomes means you need to test different ideas

The whole point of focusing on outcomes is that you have to adjust course based on the data. We have to test different options until we achieve the outcome.

If it's working, you do more of it. If not, you try something else.

But when people believe their goal is simply to meet project due dates, they often do the opposite. They define everything they'll ship in the quarter in advance and stick to the plan, even when things aren't working as expected.

They don't test new ideas or adjust the backlog based on the data.

I remember a conversation during an OKR Check-in with a client:

Team member: The infrastructure team had to deprioritize the server migration project, so we won’t be able to achieve our Key Result.

Manager: But we still have two months until the end of the quarter. What else can we do to achieve the outcome? We want to focus on the outcome, not on a single project.

There’s also the common case where a project doesn’t make a difference. They could have migrated the servers and still not have achieved the outcome.

That's why outcome-driven companies treat projects as experiments, rapidly testing ideas to discover which ones will help achieve their desired outcomes (in the product model, this is called product discovery).

Now that we've covered the difference between outcomes and projects, let's discuss project metrics.

Not all metrics measure outcomes

People often believe they just have to make their Key Results “measurable”. After all, we've been taught to focus on measurable goals.

But just because something is “measurable,” it doesn’t mean it’s an outcome. That's why we need to understand the difference between outcomes and project metrics:

Outcomes (together with their associated metrics) measure the benefit we want to create. They measure if we are making a difference.

Project metrics measure project progress. They measure how many things we did.

Here are a few examples of project metrics:

Train 100% of managers in OKR by June.

Publish 10 posts.

Move 100% of servers to the cloud by the end of Q3.

Increase the number of published APIs from X to Y.

The questions you need to ask are, are we measuring if we are making a difference? Or are we just counting how many projects or activities we did?

A real OKR communicates the outcome you want to achieve and how you will measure it

Intel created a fill-in-the-blanks formula to help people set good goals. It's the best way to explain the structure of an OKR:

I will ________ as measured by ____________

The idea is that a proper goal has to describe the outcome you want to achieve and how you are going to measure it. That's why the words "as measured by" are so important.

We could rewrite the formula as:

I will achieve this outcome as measured by these metrics.

The two OKR components, the Objective and the Key Results, fit perfectly in the “as measured by” formula:

I will Objective as measured by Key Results.

We can see that the Objective communicates the outcome we want to achieve while the Key Results show how you are going to measure it.

Or, to put it another way:

A real OKR communicates the outcome you want to achieve and how you will measure it.

For example, we could easily take the outcome we've seen before and rewrite it in OKR format:

Objective: (What is the outcome?)

Make our app easier to use.

Key Results: (How will we measure it?)

Reduce user support requests from X to Y.

Increase the % of users successfully completing account registration from X% to Y%.

Reduce time spent to complete a purchase from X to Y.

And here's a hypothetical OKR example from Uber:

Objective: (What is the outcome?)

Provide faster and cheaper rides

Key Results: (How will we measure it?)

Reduce average pick-up times during peak hours from X to Y.

Reduce rides canceled by drivers from X% to Y%.

Reduce average price/mile during peak hours from X to Y.

There is no benefit in saying your projects are “Key Results"

Let's contrast the two OKRs above with another bad example from Measure What Matters:

OBJECTIVE

Deliver awesome end-to-end workforce technology solutions and strategies.

KEY RESULTS

Implement Box pilot for first 100 users by mid-quarter.

Complete BlueJeans rollout to final users by end of the quarter.

Transfer first 50 individual account Google users to enterprise account by end of the quarter.

Finalize Slack contract by end of month 1 and complete rollout play by end of the quarter.

This is not a real OKR.

The Objective focuses on “delivering solutions” instead of communicating the outcome. The Key Results are just a bunch of projects, project metrics, and due dates.

There is no benefit in saying your projects are now “Key Results.” A project by another name is still a project.

OKR should measure the outcome, not the work

OKR is just a tool, and the results you get depend on how you use it.

How you use OKR matters: OKR can either cultivate an outcome-driven culture or reinforce a culture focused on due dates.

OKR should measure the outcome, not the work.

The best way to put this article into practice is by discussing its main takeaways with your colleagues or friends.

Here are a few questions to help:

Take a look at the existing Key Results (or goals) within your organization. How many of them are projects instead of outcomes?

Think of a recent project. Was the goal just to finish it, or to drive an outcome? What outcome were you aiming for?

Do teams inside your organization adjust course based on the data or do they stick to the plan regardless of the results?

Take a look at the metrics used inside your organization. How many track project progress instead of outcomes?

Is the way your organization uses OKR reinforcing a culture focused on projects and due dates?

Think about your company's internal processes. Are teams able to adjust plans based on results? What would need to change to enable a more outcome-driven approach?

Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments or email me.

What to read next

Our next article addresses a common challenge: What if you can’t measure the outcome?

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing if you haven’t already.

This article should be a mandatory read for every company engaging with the OKRs. I would bet that ill-designed OKR software is accelerating the perception of OKRs as a macro-project management tool as opposed to a strategic one.

JIRA caused irreparable damage to the Agile idea and I am afraid a similar fate will happen to goal management. Good intentions are not enough if implemented with bad practices in order to satisfy hungry stakeholders.

Thank you again, for the valuable article.

I worked for a company in the past that was implementing OKR. Not unlike Agile, it turned out to be a half-baked and misunderstood solution... to whatever problem we think we had.

One of my biggest issues with processes is the overuse of processes. Processes are great! Don't get me wrong. But one problem that ends up surfacing is that we become so focused on implementing and using processes that delivering actual value now takes longer to do. The funny part about all of this is that it's being sold as a way to deliver more value sooner. The opposite is often the result... from my experience.

The mere mention of "due dates" will be triggering. So I applaud you for publishing this article. Bold move.

I mentioned above about the "half bakedness" of processes like Agile and OKRs in a business: the point I want to try to make here is that due dates are business 101. I would absolutely love to believe that there is a world where businesses have less of a focus on due dates and more focus delivering outcomes and value, but I highly doubt that this will ever truly become a reality. There's no reality where business people divorce themselves from due dates for these reasons:

1. Business people believe that they NEED to know when they're going to get the thing that they're paying for. And sure, this is reasonable, but as is often the case with trying to predict the future, deliveries shift regardless. For really good examples of this, look no further than the aerospace industry. There is always shift and cost overruns.

2. Forcing functions! Due dates serve as forcing functions. Business people believe (and there is some legitimacy to this) that people won't push themselves to get work done faster/sooner without a due date. Wether the due date is a legitimate due date or not. It doesn't matter. The psychological effects of due dates FORCE people to work harder and faster... for better or worse. Often worse. The reason for that is simple: when your daily life is a constant grind, you will search for short cuts. Those short cuts are when quality starts to slip. :cough:Boeing:cough: Believe me, I know there's a lot more to it than that with Boeing, but this is certainly one aspect. Who needs bolts on door plugs anyway? Amirite? We need to ship this thing yesterday. < due date!

I've seen many business people over the years grip hard onto their due dates and any challenge to them will often be met with the excuse of "...we have external forces that make shifting the due date impossible". A full-stop, non-debatable excuse. Another eye roll.

Even if you could convince business people to stop focusing on due dates, they will find ways to keep them and hide them. One such way is renaming them. Say hello to "Sprints"! Sprints are another forcing function. They are, in effect, due dates! True story! Deliver smaller chunks of value every two weeks. Welcome to the velocity grind! Another VERY misused concept. "Take on more story points", they will tell you. Increase your velocity... uh huh :eye_roll:...

Felipe, I wish you the best of luck with this mission. I would love to see/read some examples where you've successfully convinced a business to operate this way. Though, I'm not sure I'd be convinced that they haven't found a way to hide their old habits.

Let the poo-flinging comments ensue!