To Create Better Company OKRs, Follow Jeff Bezos' Advice

Focus on what won’t change: What's not going to change in the next 10 years?

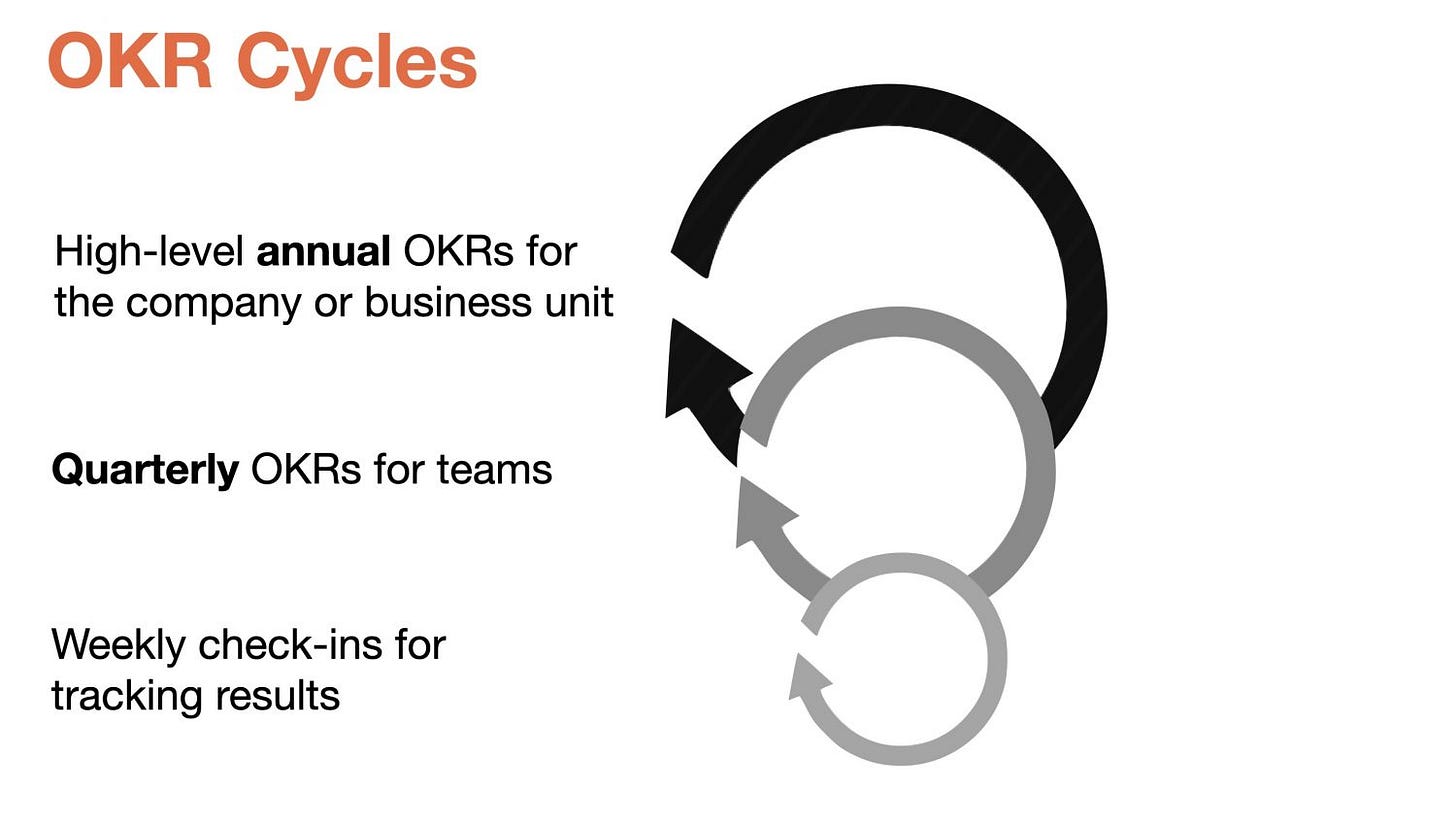

Many organizations adopt OKR because they want shorter and more frequent goal cycles. But companies often discover that using only quarterly OKRs can cause teams to miss the big picture and focus solely on what they can accomplish in three months. That is why OKR uses different cycles:

What is the best approach when creating annual, company-level OKRs?

Follow the advice of Jeff Bezos, Amazon's Founder. Focus on what won’t change:

I very frequently get the question: "What's going to change in the next 10 years?" And that is a very interesting question; it's a very common one. I almost never get the question: "What's not going to change in the next 10 years?" And I submit to you that that second question is actually the more important of the two -- because you can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time. ... [I]n our retail business, we know that customers want low prices, and I know that's going to be true 10 years from now. They want fast delivery; they want vast selection.

It's impossible to imagine a future 10 years from now where a customer comes up and says, "Jeff, I love Amazon; I just wish the prices were a little higher." "I love Amazon; I just wish you'd deliver a little more slowly." Impossible.

When you have something that you know is true, even over the long term, you can afford to put a lot of energy into it.

Bezos knows what won't change and focuses on it. His long-term goals are clear: more products, cheaper, and faster. You can think of the Kindle and things like drone delivery as means to achieve those goals. Initially, they were experiments.

Separating Strategy from Experiments

When working with my clients, I usually ask them to review their company OKRs and tell me how it went, in a short OKR Retrospective.

I often hear comments like: "Oh, we gave up on the first KR... The fourth one was no longer our strategy. And we didn't have the resources to go after the last one."

When this happens, it becomes clear to me that they don't know how to use different OKR cycles. The beauty of the model is that it allows companies to separate validated strategies, things that won't change, from experiments.

While every strategy is, in the end, a hypothesis, companies needed data showing that the approach works at least on a small scale. If you don't have that data, you can run an experiment during a few quarters before committing the whole company to it.

Before including a Key Result in your company OKRs, ask yourself:

Have you validated all the components of this strategy?

Do you have the data to back it or it is still an experiment?

I had the following dialogue with a client a few years ago:

Client: We have included this Key Result at the company level: Sell 30 million through partners. That is 30% of our revenue target for the year.

Me: Really? How much did you sell through channels last year?

Client: Zero. We have never used partners before.

Me: Why do you want to bet such large part of your revenue target on a non-validated idea? We need to test it first. Let's include it as a team-level KR for Q1 to see if you can find partners that generate revenue. If it works, you can put more resources into it.

Client: Ok. Let's keep our options open.

Focus on What Won't Change

A good strategy is a blend of commitment - to give you focus - and flexibility. Although OKR will not help you formulate your strategy, different OKR Cycles can help you separate the components with stronger evidence from the more uncertain ones.

To create good OKRs for your company, remember Bezos advice and focus on what won’t change.

Although OKRs should not be written in stone, this approach will force you to gather data before committing, and that is always a good thing.