You can find the first part of this article here. This post is also available in Portuguese.

The "more is better" mindset towards priorities is sabotaging your organization's ability to focus. And it's costing you way more than you realize.

This worldview suggests that companies can achieve more faster by working on dozens of priorities at the same time than by focusing.

People with the more is better mindset believe that “prioritizing“ means adding things to an already long list of priorities.

As Rich Mironov points out, they want to "prioritize in":

“These are really important (to my department or division), so we need to approve them all” (…)

Prioritizing in is about getting agreement to do more, especially what’s on my list.

How can we help people understand the importance of unlearning this way of thinking, especially senior leaders?

For years, I've been using a powerful exercise to challenge this mentality and illustrate the impact of focus—using nothing more than a few bottles of whisky.

Learning focus with whisky bottles

The 12 bottles of whisky exercise was created by my friend Paulo Caroli, a principal consultant at ThoughtWorks and a whisky lover.

One day, as he poured himself a dose of a 12-year Macallan, Caroli asked himself, “How long does it take for me to drink one bottle of whisky on average?”

I'd like your help with this question. Here are the details:

Caroli’s whisky cabinet has enough space for 12 bottles of whisky, and he always keeps it full.

Whenever he finishes a bottle, he removes it from the bar, opens a new one, and adds the new bottle to the bar. Every year, he drinks six whisky bottles.

Now, try this quick exercise:

If the cabinet holds 12 bottles of whisky and Caroli drinks 6 bottles per year, how long does it take for him to drink 1 bottle on average?

Please select an option before continuing:

A. 6 months

B. 3 months

C. 2 months

D. 1 year

E. 2 years

We'll discuss the answers after this short break.

Move from projects to outcomes

Develop the muscles and mindsets you need to focus on outcomes and get better results with OKR by attending one of my workshops.

I designed them to help you unlearn the model where teams are always chasing multiple conflicting deadlines.

Instead, we'll shift to a model that gets everyone moving in the same direction, focused on the outcomes that really matter.

Contact me to organize an in-company workshop or keynote for your team.

If you’re like most people, you chose option C, two months.

Since Caroli drinks 6 bottles per year, and there are 12 months in a year, it seems logical that it would take him 2 months to finish each bottle (12 months ÷ 6 bottles = 2 months per bottle).

That would be the correct answer, as long as he kept drinking from one bottle.

What if he drank from different bottles each time instead of focusing on a single one?

Drinking from all 12 bottles in parallel, it would take him two years to finish each bottle on average.

Working sequentially vs in parallel

Imagine Caroli had a brother who drank from all bottles in parallel while Caroli drank sequentially, finishing a bottle before moving on.

On average, Caroli would finish one bottle every two months while his brother dealt with several partially drunk ones. By the time the brother finished his first bottle, Caroli would have finished 12:

Have you ever been to one of those organizations where people are always complaining that “nothing ever gets done around here”?

Where a simple website update can take months, and product features can languish in development for several quarters?

The answer may be quite simple: they are drinking from 12 bottles at the same time.

Lack of focus has real costs

Organizations often don't realize how much lack of focus costs them, even as they work hard to cut expenses elsewhere.

The cost of working on multiple priorities simultaneously can be proven by more than just visual examples.

MIT professor John Little proved mathematically what is known as Little’s Law: in a stable system, there is a linear relationship between the number of items in the system and the average time each item spends in the system (the lead time).

Simply put, the more bottles you drink from in parallel, the longer it will take to finish each one.

This is an example of what economists call opportunity costs. For every hour you spend working on a "priority" that's useful but not critical, you surrender an hour of working on what will create real impact.

In real life, the burden of lack of focus is even greater. Executives and teams also have to deal with coordination costs (the effort needed to synchronize work across different teams) and context-switching costs (the productivity loss when shifting attention between different projects).

From "more is better" to "start less, finish more"

Little’s Law and the 12 bottles exercise show the impact of shifting our mindsets from “more is better” to “start less, finish more” (which is the title of a book by my friend Dan Montgomery).

Start less, finish more means that if you limit the amount of partially done work—also known as work in progress (WIP)—you'll improve your throughput.

Limiting WIP is like restricting the number of whisky bottles you drink from in parallel. By limiting the number of partially drunk bottles, your WIP, you'll finish each one faster.

The importance of limiting WIP has been common knowledge in lean manufacturing and technology circles for many years. In fact, strong product teams often limit the number of items or user stories1 they work on at the same time.

But few organizations manage WIP at the company level, handing out priorities like candy on Halloween.

However, senior leaders can unlearn this mindset, like the executive who had an aha moment during one of my workshops:

Maybe instead of having 20 projects that move slowly, we should have 3 that move fast.

“We have multiple teams, so we can work on multiple priorities”

Some people argue that their organization can pursue many priorities at the same time because they have multiple teams. "We'll dedicate a few teams to each priority," they'll say. "That way, nobody will be overwhelmed."

There are two big flaws in this argument. First, spreading resources too thinly means you'll never have enough to make significant progress on anything. The peanut butter approach is not a strategy.

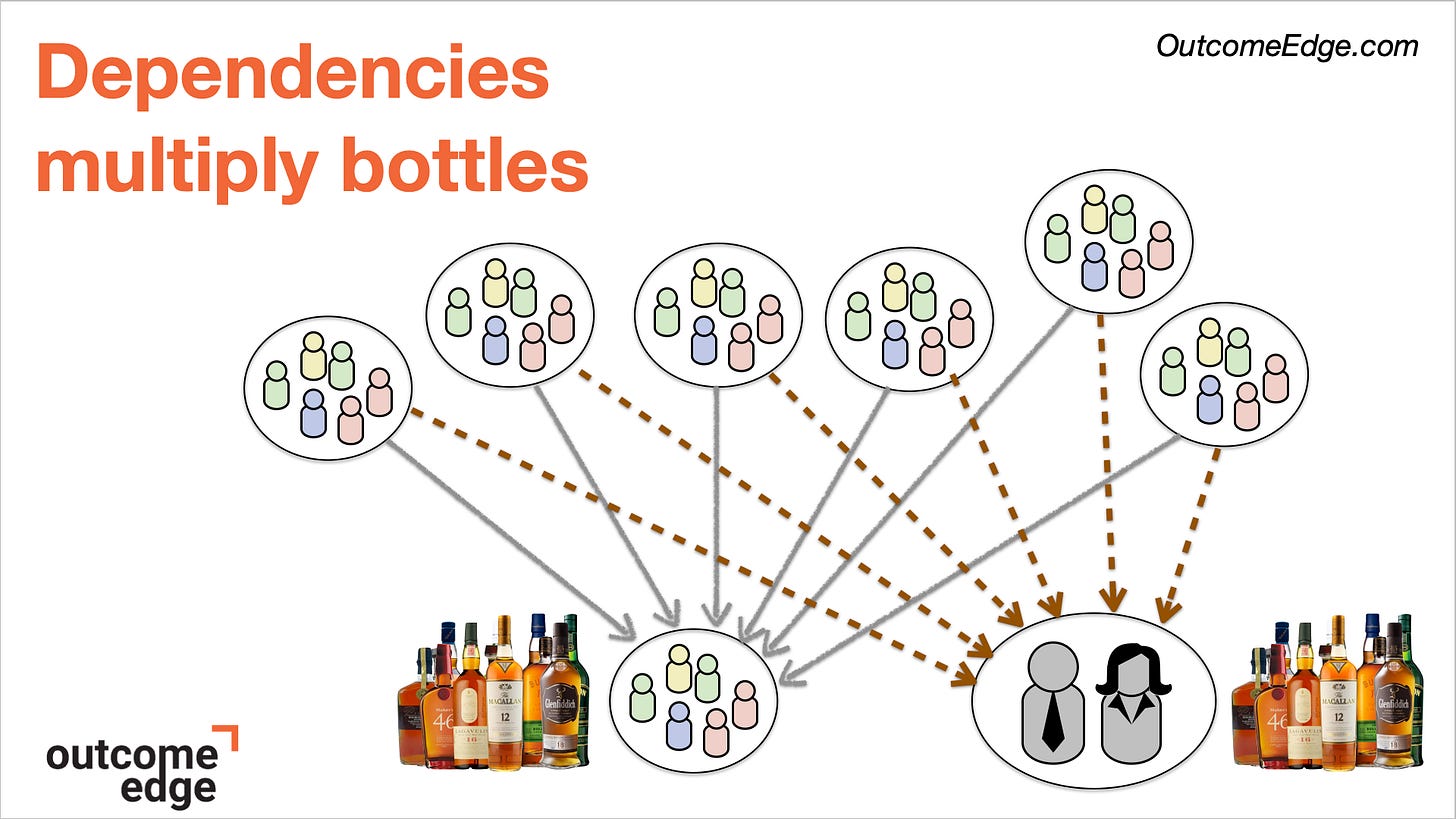

Second, in real life, teams have dependencies. To make progress, they require effort by someone else—whether it’s building something new, providing input, or making a decision.

Dependencies plus multiple priorities mean someone will end up drinking from too many bottles in parallel.

It can be a platform team serving other product teams2. Or it can be an executive, stakeholder, or central function that has to review the work before it can continue.

In either case, many people will be left waiting until the overwhelmed teams and stakeholders slowly empty all these bottles.

Since most organizations have far too many dependencies, whisky bottles multiply like rabbits. Soon, everything slows to a crawl.

Focusing and limiting WIP is a journey, but you can make progress in gradual steps. You have to eliminate dependencies instead of managing them, as Amazon famously did.

And as we'll see in the next article, you also have to build the muscles to say no—even to ideas you think are phenomenal.

In the meantime, ask yourself: How many whisky bottles are you and your team drinking from in parallel?

Links:

Rich Mironov: My Next Word to Retire is 'Prioritization’.

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend and consider subscribing if you haven’t already.

In software development, work is often broken down into small, manageable pieces called "user stories." A user story describes a feature or piece of functionality from the perspective of the end user.

There are two basic types of product teams. Experience teams focus on directly solving problems for customers and users. Platform teams provide the tools and capabilities that empower experience teams to solve those problems more effectively.

Thanks for providing a written version of the example that you mentioned in a talk in 2019. Focus is hard but crucial!

Great article!! We have this discussion often and I love your metaphor with the bottles. Thanks